For most people, their idea of what economists do is make dubious predictions about economic growth and inflation. The predictions are dubious, but in any event that is not what most economists do. We need not dwell on what they do do.

There is a big cottage industry devoted to forecasts of short-term, quantitative changes. Will inflation tick up by one-tenth of a percent a month, or not. A lot of money can ride on such predictions. It should be clear this sort of thing is of little interest to most people. The onset of inflation is noted, but few put any stock in the predictions, and for good reason.

My theory about the prediction business is that people pay for those things because it gives them the basis for a rule on how to make speculative financial transactions. Or because it justifies what they wanted to do in any event, but lacked a plausible justification. People once told me that consultants are hired to provide an outside voice in support of something somebody inside the organization wanted done in the first place. Naturally, the enterprising consultant will figure out what the customer is after by way of advice.

The other sort of prediction pertains to broad movements over the long term, and particularly to the possibility of a breakdown — another recession, or worse. This would be of interest to any political strategist.

Marxian economics is widely held to confidently predict the total crash of the capitalist system. This is a gross simplification. What Marx does do is propose tendencies that contribute to collapse.

Many radicals have always staked their politics on the specter of a big crash. The psychology here — and I am not excluding myself — is that big faults in capitalism demand big answers, and big answers will only be politically possible in conditions of collapse. The reasoning is circular.

Such radicals are, or were, living in the past. In pre-war Europe, mass strikes were a real option. There were a few. They were blowing up in Russia. How useful they were we need not look into. My point is the state of labor organization, both in social-democratic parties and in the trade unions themselves, was far deeper than anything on view today. Moreover, as I noted in my previous post, the unions themselves were the least amenable to general strikes as political tools. They were afraid of repression, and they were more focused —following their members — on incremental gains rather than on risky Revolution.

These days the speculation about general strikes is really a confession of political ineptitude. I do not believe that those calling for general strikes themselves believe such a thing is possible. So why the talk?

Going back to Europe before WWI, the mania for mass strikes was primarily the property of anarchist tendencies and groups. It was partly a rejection of parliamentarism — conflated with reformism. These days we observe the same thing. Reforms at the national level require entry into the Democratic Party. The election rules preclude anything else. But if you boycott the Democrats on principle, you’re out of the reform business.

I was interested to read in Schorske that for a period, the sizable SPD presence in parliament was mostly what we now call performative. The purpose of getting elected was to promote radical objectives that would never have a chance of legislative enactment. This worked politically for a while, contrary to my priors on this subject, but with further growth in the SPD and the unions, the interest shifted to tenable reforms. The orthodox Marxist position, espoused by Karl Kautsky and Rosa Luxemburg, that capitalism was immune to reform, was jettisoned, especially by the German trade unions, meaning the workers themselves.

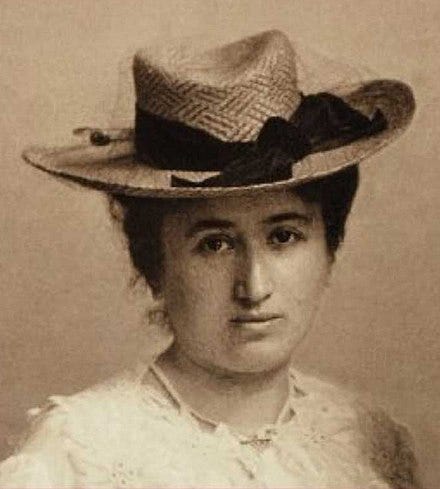

Luxemburg was the leading voice in the SPD on the question of mass strikes. As a youth, I read her book on the subject. It was thrilling. It provided you with a vivid picture of what a revolution would look like. Alas, if applicable at all, it was to a bygone historical period. Nothing resembling her scenario was a plausible expectation for the U.S., especially after World War II.

(I dig the hat.)

It’s interesting to note that, according to Carl Schorske, Luxemburg came around to the idea that Radicals cannot “call” a general strike. Their occurrences are rare and unpredictable. She leaned towards what is sometimes called a “spontaneist” view. One take on this mindset was that a small group of radical cadres could prepare for a mass uprising, could prepare to just take it over and lead it to socialist victory. The delusions are compounded.

What if no collapse is forthcoming? Then you look foolish, like those cartoons of vagrants holding sandwich signs saying “The End is near.” Your political strategy will also be deficient, depending on the expectation that utter chaos from an economic collapse will stimulate progressive politics.

The fact is that being severely beaten down does not turn one into a socialist. In fact, the results could be quite the converse. I used to think it was wrong to consider the MAGAs as ‘populist’ in any way. I no longer think that. The Mike Kazin book is balanced in this respect, making clear the variety of populisms in the U.S., both left and right. Today’s MAGAs are motivated by class antagonism towards educated elites and an assortment of demographic sub-groups. They want somebody on their side. The Democrats, especially their poet laureate Obama, counter with soaring, universalistic, above-the-fray rhetoric that falls flat.

Second, we had a Great Depression in the U.S. that was indeed associated with a lively labor movement and radical movement, but revolution was never in the cards. This was even less conceivable during the very severe ‘Great Financial Crisis’ of 2008. All we got were the pathetic ‘Occupy’ encampments. Third, the government is better-equipped to deal with breakdowns, thanks to Keynes and his followers. The tools in question are geared to spikes in inflation or unemployment. What’s missing, or at least in question, is how to deal with financial meltdowns. The biggest threats to the system — I would say are ecological, pandemics, or financial meltdown — are even less foreseeable than routine fluctuations in GDP or the price level.

Thanks to Covid and the war in Ukraine, we had yet another episode of deep recession in 2020. As before, no left-facing revolt was on the horizon. The government, first Trump beset by a Democratic Congress, then Biden in 2021-22 with the benefit of that Congress, did useful things. Those who neglected those struggles, perhaps for the sake of local matters like slumlords or police misconduct, were basically AWOL from politics.

The dilemma for socialists now is that the short-term fluctuations in GDP, the preoccupation of professional forecasters, are of little interest. The possibility of a big crash is impossible to predict and indeed may never transpire. Moreover, if it did, the government has devices to deal with it, and we have already seen that political opinion is not motivated by material well-being, at least, not in any simple way.

The MAGA voters were happy to accept the risk of death or disability from Covid, rather than support elementary public health policies. Now we are seeing a replay of that with the anti-vax insanity and kids contracting life-threatening measles. Once again, economic distress or material self-interest need not drive people to the Left.

The job is how to persist for the long haul, without the benefit of a crisis. It’s a marathon, not a sprint. I note that in past crises, the Left failed to show up in any case, but that just elevates the problem of How to Persist.

Recall the old philosopher

on the radio ?

"Social democracy

can't live with it

Can't live without it "