I am one of those idiots. In grad school, my macro teacher, the illustrious Martin J. (not Neil) Bailey (R.I.P.), an economist of the then-infamous “Chicago School,” focused obsessively on an austere six by six equation macro model with no foreign sector (consumption, investment, money demand, money supply, government spending, and I’ve forgotten the other one).

I never delved into international trade and such, choosing public finance for my field of specialization. To be honest, exchange rates confuse me. What do you divide by what. The most I can usually remember is that if the dollar weakens, that’s good for exports and the workers who produce them. If it strengthens, that’s bad for workers but good for consumers of imports. All things considered, a weaker dollar is what the Left should favor. It’s a class thing.

I rarely travel, so it seldom becomes a practical concern. I’m not a big spender. When I go to Europe I just buy what I want, within reason (no “haute cuisine” or lodging above $200 a night, thanks), and let the credit card companies sort out the conversions. They seem to do that well enough. If you travel, you want a stronger dollar. You can buy more of the local shekels and the stuff that buys. More Croque Monsieurs (sic):

A friend alerts me to the relevance of exchange rates for the big Trump tariff spectacle in prospect. Exchange rates, below the radar of most citizens, have profound significance for tariff policy. Briefly put, a change in those rates can entirely offset the impact of a tariff, whatever you think that is. Moreover, rates are damn complicated.

For imports to come into the U.S., the importer must pay in and the exporter must accept U.S. dollars. A Chinese air fryer priced in Chinese currency (the yuan a.k.a. the renminbi, currently going for fourteen cents), say 1,000 yuan or $140, becomes more expensive if the price of yuan goes up (the dollar falls), say to fifteen cents, against the renminbi. You need more dollars — $150 — to defray the 1,000 yuan. To sell into the U.S., the exporters add the tariffs to their prices, and the importers pay that and duly pass along the higher prices to their buyers.

The purpose of a tariff is to do just that — raise the cost of imports. A jolt to the price of imports raises the average consumer price level in the U.S. A ten percent tariff on air fryers raises its price in dollars by $14, paid by U.S. consumers. To attenuate the effect of the tariff, the exporting country can weaken its own currency relative to the dollar. For instance, China might accept thirteen cents to buy a yuan, instead of fourteen. How could it do this? By altering exchange rates.

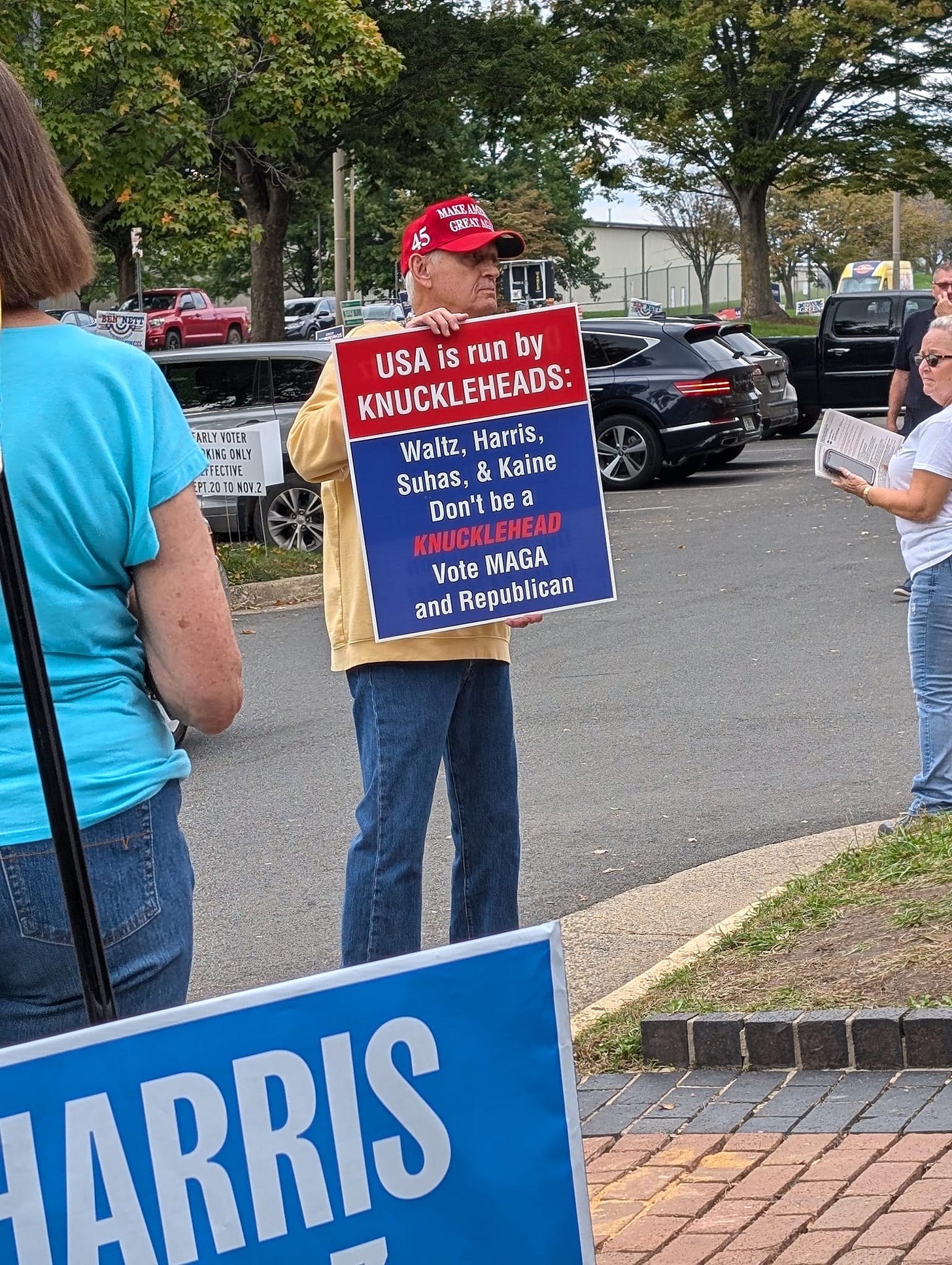

Following Professor Bailey, who was actually a very lucid instructor aside from being a right-wing character, I like to distinguish between a single bump in the price level and inflation, an ongoing rise in the price level. The Bidens would have liked to make this distinction too. Nobody bought it. Inflation disappeared but the price level remained elevated. I explained this to a MAGA gentleman while working the polls seven or eight weeks ago, and he called me a Marxist economist. This guy:

It was a civil discussion. His top concern was boys infiltrating girls’ sports teams. Hunky gay boys in the boys’ showers, no problem. I abandoned the conversation when the specter haunting Virginia, Marxism, came up.

Getting back to tariffs, the idea is to advantage U.S. manufacturers, who enjoy some combination of higher prices to match up to the imports’ raised prices, and greater sales if they choose that opportunity to offer a competitive discount in their own prices.

Cheaper dollars, a dollar that buys less of another currenccy, mean more expensive foreign currency and raise the domestic cost of imports. At the same time, cheaper dollars stimulate U.S. exports. Foreigners can buy U.S. exports for less of their own currency.

I can’t be sure how much DT’s lizard brain understands, beyond the notion that ‘deficit’ = bad, surplus = good, but he probably does know that exchange rates affect trade. Notwithstanding his blather about the trade deficit and his use of tariffs, the trade deficit hardly changed over the course of his first term.

The problem for “Tariff Man”* is that China and other exporters can diddle their exchange rates to reduce any losses from higher tariffs, and they are not incompetents. The can make their own currencies fall relative to the dollar by instructing their banks to sell yuan or whatever, pushing down its price and the dollar’s price in yuan up. This is exactly what happened in 2018-19. The yuan got cheaper, the dollar appreciated. In fact, this trend has prevailed since the November election.

One of the few substantive bees in Trump’s bonnet, from the very beginning, was the trade deficit — the difference between what the U.S. buys and what it sells from other countries. If we buy more than we sell, that’s called a deficit. The trading partner takes the difference in dollars, typically converted into U.S. Government bonds.

MAGA workers might like the sound of a “strong dollar,” but it means the products they manufacture or harvest for export become more expensive for foreigners. It also makes imports cheaper, offsetting the impact of tariffs. China can make the dollar stronger by making the yuan weaker. Traditionally, a currency devaluation is one type of offensive “beggar thy neighbor” trade policy.

An increasingly strengthening dollar also creates interest among other nations in devising an alternative “reserve currency” so they don’t need to keep buying dollars indefinitely to facilitate world trade. The dollar remaining the dominant currency in world trade provides a great economic advantage to the U.S. Trading partners are willing to accept dollars by selling us their stuff. They get dollars, we get stuff; what’s not to like? The supreme economic irony of “America First” is that it could dethrone the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. Talk about screwing the pooch.

Trump is aware of this threat and displays his usual bluster, warning other countries not to construct alternative currencies. More broadly speaking, however, this is all way over his head. And mine too. This post significantly simplifies the forces at play. Other major factors entailed include interest rates, world trade in major commodities such as oil, and geopolitical relations. Attempting a big, aggressive policy in this realm conjures up the proverbial image of the one-armed paper-hanger. Or the blind man who thinks he has an elephant by the short hairs, when he only has the whiskers.

The Left is ambivalent on tariffs. There is a potentially constructive use for them, to bolster U.S. manufacturing, exports, and working class wages. A few liberal stalwarts in the Midwest such as Senator Sherrod Brown were sympathetic, another good deed that did not go unpunished. There are also progressive trade activists who can be persuaded to endorse tariffs. My own outfit, the Economic Policy Institute, was in the tent, pissing out. Unlike EPI, however, some of the activists do not seem to have heard about exchange rates.

If I’ve fucked up this explanation, corrections are welcome.

* * *

*Don’t forget that for all the wailing about Trump’s tariff proposals, the Biden Administration held over most of Trump’s tariffs from his first term, estimated at an average of 15 percent. For all that, you could not in that policy find any harm to employment (nor during Trump’s first term, before Covid). Those impacts are hard to trace, in any event. The chief political fallout of Trump’s tariff increases will stem from possible spikes in the price level and as mentioned above, the international economic earthquake of a new global reserve currency. On the mundane inflation level, just keep this bit in mind, from my neighborhood in Virginia:

If the price starts popping after Trump’s inauguration, it will be fun to see all the MAGAs try to fight back against the inevitable online deluge of photographs showing elevated prices.

Thanks for the post Max, (after a 40 year career devoted to too much modeling of international trade) I have some technical notes.

1. At 10% tariff on a $140 (retail) microwave (by itself) would not raise the price by $14. About half of the retail value of appliances are transport and trade margins added within the US . So IF the importer passes the entire tariff on to consumers the retail price would increase by just ~$7.

2. As Trump insists, importers do not necessarily pass the entire tax onto domestic consumers ("in theory" retailers could also take a haircut). Through history we have seen tariff pass-throughs that are neither instantaneous nor ultimately complete depending on -- as Trump says -- market conditions (demand and supply elasticities).

Microwaves are a good example. Since nearly all of them are manufactured in China (low price-supply elasticity) and because when a US consumer needs a new microwave they need a new microwave (low demand-price elasticity) market conditions would imply rapid and complete pass through. Indeed, multiple research studies on the Trump-Biden tariffs indicate that pass through was both remarkedly rapid and virtually complete. (There are MAGA studies out there that use a raw -and timeless - version of GTAP that assumes no pass-through and therefore a large terms-of-trade benefit to the US. I don't think anybody buys them.)

3. The own-currency appreciation one expects after a country raises tariffs occurs automatically; there is no need for trade partners to manipulate currency values (though that may also occur). Tariffs increase demand for the home currency and reduce demand for the foreign currency, driving up the home currency, voila: appreciation. Moreover, if the tariffs do cause a transitory uptick in inflation, any increases in interest rates (by explicit Fed action or just through the market because of the inflation effect) will increase demand for the local currency. This effect is a powerful stabilizer which reduces net exports just as the economy is hot. High interest rates are the main reason the dollar has been so strong recently, and why -- notwithstanding the imposition of new tariffs -- we will probably see widening trade deficits under Trump at least as long as the economy grows.

4. The bigger dangers that tariffs pose for price stability and employment is (a) the behavior of domestic producers (who as you point out now have free rein to raise their own prices), (b) foreign governments who retaliate with trade barriers of their own (requiring new subsidies for farmers?) and (c) the corruption that may or may not occur as the home government adjudicates who gets breaks from the taxes and who does not (remember how we used to chide other countries on rent-seeking).

Heroic effort

Facing revelation quality eventuality

Jousting with

a 5 eyed 7 horned

flying purple people eater